Welcome to Dachau

The old black metal gate stood menacingly ahead of me and creaked as it swayed gently in the hot June breeze.

The single gate could fit only one person through at a time. Hesitantly, I stepped onto the dirt on the other side of the gate, as I did the summer breeze suddenly seemed to stop.

Unexpectedly, I felt a chill run down to my very core.

I took my first steps into the vacant memorial site, a large open space, approximately five acres in area. Lush green trees were lined along the perimeter of the property, a bit closer and just beyond the entrance, stood some old timber buildings. It was the wide open spaces that I had not expected.

Silence. There was nothing but silence. It was eerie, like a cemetery.

By stepping through that black gate, I had just set foot onto the site of one of the most infamous locations of the 20th century. A place where untold atrocities and crimes were committed.

This was Dachau, the original and first of Hitler and his Nazi regime’s notorious ‘Concentration Camps’.

‘Why Would You Want To Go There?’

I had seen the movies, seen the documentaries and heard the stories.

Being a student of history, ever since I was a boy, this place had a sense of familiarity.

As I grew up, the stories from the Second World War were still told, by veterans who were still alive and their families.

My family has a rich military history, as many do in New Zealand, both in distant relatives who served and even my Grandad, who was a tank driver in World War Two.

Having always dreamed of visiting battlegrounds, war memorials and other historical sites on a trip around Europe, a visit to a Concentration Camp memorial always interested me.

‘Why would you want to go there?’ I would often be asked if it ever came up in conversation.

The honest answer was I didn’t know.

At times, I would try and come up with a reasonable explanation as to why, but for some reason, I could never find the right words. The best answer I had was a silent one. I would only be able to find that answer by visiting.

A Brief History of Dachau Concentration Camp

In one of recorded history’s most tragic periods, Adolf Hitler and the Nazi regime were responsible for the genocide of six million Jews between 1941-1945.

A number that equated to approximately two-thirds of the European Jewish population at the time.

This tragic part of history did not happen overnight, as from 1933, Hitler and his Nazi regime began to establish what became over 44,000 incarceration sites across Germany to imprison and eliminate perceived ‘enemies of the state’.

These camps served different purposes.

Some were forced labour camps (brought on by the labour shortage at the time). When the war started, some were utilised as Prisoner of War camps.

The most infamous of all were the dreaded concentration camps. These camps, on some occasions, doubled as killing centres for the Jewish population.

In 1933, Dachau was the first of these concentration camps to go into operation.

Located only 10kms from Munich, the Dachau Concentration Camp became the prototype for future camps, including Treblinka, Sobibor and Auschwitz.

Exploring Dachau Concentration Camp

Taking a deep breath, I pressed ‘1’ on my audio guide and slowly started making my way around the camp.

At designated locations within the camp, a brief history was explained, in detail, by a narrator. Dozens of other recordings were recollections from prisoners, detailing their brutal experiences within the camp grounds.

Initially, you enter the ‘Roll Call’ area, a large open area.

In this area, prisoners were forced to stand for hours every morning and every evening. This was the centrepiece of the camp. On the right-hand side of the roll call area were the camp administration buildings.

Today, these buildings have been restored into a remarkably poignant, yet brutally honest museum detailing the history of the Dachau Concentration Camp.

To the left of the roll call area, sits a restored prisoner barracks. Long since gone, the concrete foundations of the other thirty-two barracks lie parallel to each other, bordered by green trees and stretch down the camp grounds.

Whether you were in the prison barracks or in the administration buildings, everywhere had a story.

Listening to and reading about stories of suffering and tragedy alongside remarkable bravery tugged at your emotions. It wasn’t all sad though, some of the most important stories were about hope.

These stories are all parts of the Dachau story.

At times, my mind would drift off occasionally. My mind would get lost in the moment as I tried somehow to understand how human beings could willingly partake in such atrocities against our fellow man.

In the same location I was standing in.

The uncomfortable thing I recognised is it didn’t happen a long time ago.

Looking around the camp grounds, you could see other visitors dotted around at different locations, but the vastness of the space still made it an incredibly lonely experience.

I visited Dachau with my partner and son, but we barely said a word. When we did speak, it was in whispers as if we were in a library. It felt strange, no one hardly got close enough to be in earshot, even if we spoke like normal.

It just felt like the right thing to do.

You could feel the ghosts of the place at every turn, with every gust of wind, I could sense something else there. Nothing ghoulish, nothing scary, just an overwhelming sense of incredible sadness.

The Long Path

Walking into the prisoner barracks was a humbling experience.

The barracks have since been rebuilt but are identical to the ones used. Even though the barracks on site aren’t original, it wasn’t hard to imagine the horrific conditions the prisoners were expected to live in.

Seeing the facilities and how they lived their lives in such suffering, for years on end in some cases, affected me emotionally in a way I had never felt before.

Walking past the concrete foundations of the barracks, I followed a long dirt path, about 200 metres long.

Tall trees gave us a little shade walking down the path to give us a break from the blazing sun. I knew what was waiting for me at the end – the gas chamber and cremation block.

Feeling a chill down my spine, I could see the tiled roof of the infamously named ‘Barrack X’ as I approached, hidden behind the row of green, summer trees.

Before reaching the gate of the crematorium area, I felt a sense of hope as I passed a memorial garden.

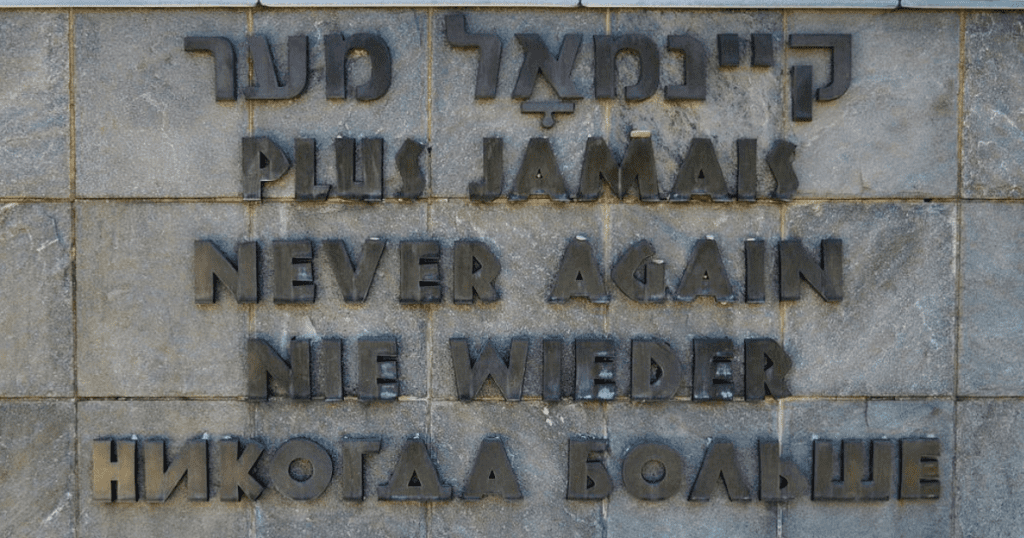

A collection of memorials from across the faiths and globe stand silently, remembering the people who lost their lives here. Jewish, Protestant, Russian Orthodox and Christian memorials are impeccably maintained, reminding us to never forget.

We should never forget.

The ‘Path of Death’

The chill I had down my spine earlier only increased, to the point where I had to stop. To stop and take a couple of breaths before proceeding.

Crossing a small bridge from the prison camp itself, I entered the cremation area of the camp. A place where thousands and thousands of bodies had been disposed of during its time in operation.

The building itself was unremarkable. It was a light brown, single-level rectangular-shaped brick building with a large single chimney. The design looked like many buildings I had seen in many places before.

My breathing slowed noticeably, as I took a few more paces forward.

Looking around me, I couldn’t see anyone. My partner and son chose to give this section a miss so I was on my own.

Not for the first time that day, it felt like I was the only person around.

Before entering the crematorium building itself, a brief detour took me through the ominously named ‘Path of Death’.

The ‘Path of Death is a memorial walk that doubles as a memorial site and a gravesite for thousands. It is also the location of several execution sites used during its time in operation. Plaques lay beside the grassy path, with names like ‘Blood Ditch’ and ‘Pistol Range for Execution’ left me in no doubt about what had occurred in that area.

Lush, green summer leaves amongst a small forest blocked out the hot sun to give the ‘Path of Death’ today a quiet, even peaceful atmosphere.

Quite the opposite of what happened between 1933 and 1945.

The Gas Chamber

Entering the cremation building from the left, I entered a large, cream-painted room.

My first impressions were it reminded me of a sports changing room back home. This first room was designed for prisoners to disrobe and remove their clothes in preparation for the shower they had been told would happen in the neighbouring room.

The word ‘Brausebad’ was stencilled above the single, green door that stood on the right-hand side of the changing room.

Later, I learned that the English translation was ‘Shower’ or ‘Shower bath’. Innocent enough indeed. The true functionality of the room on the other side of the door was very different.

I could hear the muffled chat of fellow visitors outside the building as I stepped foot into the next room, the supposed ‘Shower’. Walking on the tiled floor, I could hear my footsteps echo in the empty room.

You could have heard a pin drop.

I stood and stared for a moment, deep in thought. The reality hit me that I was standing in a gas chamber.

A gas chamber built and designed for only one reason – the mass extermination of prisoners.

A flood of emotions and thoughts came over me for the brief time I stood there. All alone. My eyes darted around the room where I noticed the fake shower heads on the ceiling and the small drainage pipes on the floor.

It actually looked like a shower which only confused my thoughts even more. After a few seconds, I was distracted by a couple of other people as they entered the room, breaking me out of the spell I found myself in.

The official record is that the gas chamber was never used in Dachau. Some witness reports tell a different tale to the official one, with the gas chamber reportedly being used in 1944.

There will probably never be a definitive answer, as the Nazis did a pretty good job destroying as much evidence as possible in the final stages of the war.

I quickly hustled away through the final door and into the cremation room.

Five brick crematorium ovens are in this room, with their solid iron doors open. Emotions were high once again. Anger, pain, sorrow.

They were all there.

The crematorium was a room of death and it felt like it. I recognised this crematorium from pictures and books – the images of bodies piled up in these ovens is an image you can’t unsee.

Goodbye to Dachau Concentration Camp

It was now time to go.

Few words were spoken as we made our way through the camp, heading for the exit. An exit that thousands and thousands of people never got to enjoy when the camp was in operation.

Yet here we were, walking out the front gate.

I felt exhausted by the time I left. Walking out with my young family, it felt like I had held my breath the whole time. There were no expectations when I visited, all I wanted was to experience it, to try and gain a new perspective.

That is what happened.

It is an experience quite unlike any other. Dachau left me with a mixture of emotions. The sadness is the overwhelming one but I left with something I hadn’t quite expected.

I left with a genuine sense of gratitude and gratefulness for the life I had lived.

The life I have been able to live. The life that millions across Europe did not get to enjoy.

The Dachau Concentration Camp has been faithfully maintained and restored as a memorial by volunteer groups and the federal government.

There is no hiding from Germany’s past, but Dachau now serves as a reminder to future generations of just what human beings are capable of. World War Two is a painful memory for Germany, yet places like Dachau are so important to be remembered.

For a unique, sobering but educational experience, the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial delivers a travel experience quite unlike anywhere. \

It will shock you, it will challenge you, but most of all it will change your perspective on the world.

For the better.

How Do I Get To Dachau?

Dachau is only twenty minutes from the centre of Munich in Southern Germany.

By public transport, catch the S2 train from Munich’s central station ‘Hauptbahnhof’ to Dachau station. From there, the 726 bus towards Saubachsiedlung takes you directly to the memorial site. The link below can help you plan your journey from Munich.

https://www.mvv-muenchen.de/en/index.html

When we visited we drove from our campsite which was only ten minutes away. Parking is available in the car park next to the memorial site for €3.

What are Dachau’s Opening Hours?

The Dachau memorial is open from 9am – 5pm every day, only closed on 24 December.

What is the Admission Fee to Dachau?

Entry is free.

To enhance my visit, I hired an audio guide for €4.50 which I found was well worth it.

There are several other options for tours of the memorial site, including individual, group and guided tours. See the link below for these options and other ways to experience Dachau (even from your laptop at home).

https://www.kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de/en/your-visit/faq/

Can I Take My Children to Dachau?

It is recommended that children be accompanied by parents throughout the memorial site. My son was only eighteen months old when we visited, but he was asleep most of the time. Some content within the grounds is not recommended for children under the age of 13.